Oddball Films and guest curator Landon Bates bring you Solo Cinema, a program of loners,

drifters and on-screen dreamers with cast comprised

of a band of outsiders. This

collection of films celebrates the solitary, and salutes the secluded. The cinema, after all, is our sanctuary: the

abode of the awkward, shelter for the shy.

And, who better to state this theme than that perpetual wanderer, that

lone wolf, the Tramp? In The

Tramp (1915), Chaplin’s iconic hobo-hero saves a farm girl from a group

of thieves, and, welcomed into her father’s house as a gesture of his

gratitude, Charlie finds the prospect of a new home glittering (mirage-like?)

on the horizon. The Tramp will be

succeeded by two other weary travelers, likewise looking for a place to settle

down: that eponymous duo of Roman Polanski’s brilliant early short, Two

Men and a Wardrobe (1958); undoubtedly influenced by Chaplin’s

slapstick antics. In this melancholic

comedy, our pair of pariah’s, always lugging a beloved wardrobe, just can’t

seem to find their niche in the modern city.

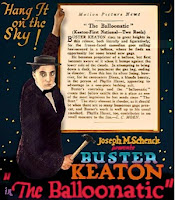

The Balloonatic (1923) is classic Buster Keaton. With gags galore, this film finds Buster bumbling

through each frame, finally whisked away by a rogue hot air balloon and dropped

into the woods to fend for himself. And,

finally, Buster’s balloon gives way to another: The Red Balloon (1956),

wherein a young Parisian boy’s best friend is his big red balloon. Theirs is a tender friendship only a special

sort of child could have, and one that ends up drawing the hostile attention of

humorless adults and envious peers. Before

the actual screening begins, we’ll be running Shy Guy (1947), an

educational film starring Dick York (of TV’s “Bewitched”), designed to bring

the antisocial adolescent out of his basement.

We similarly encourage you to emerge from yours, and enjoy—with us,

together--this evening of longing and laughter, melancholy and mirth.

Oddball Films and guest curator Landon Bates bring you Solo Cinema, a program of loners,

drifters and on-screen dreamers with cast comprised

of a band of outsiders. This

collection of films celebrates the solitary, and salutes the secluded. The cinema, after all, is our sanctuary: the

abode of the awkward, shelter for the shy.

And, who better to state this theme than that perpetual wanderer, that

lone wolf, the Tramp? In The

Tramp (1915), Chaplin’s iconic hobo-hero saves a farm girl from a group

of thieves, and, welcomed into her father’s house as a gesture of his

gratitude, Charlie finds the prospect of a new home glittering (mirage-like?)

on the horizon. The Tramp will be

succeeded by two other weary travelers, likewise looking for a place to settle

down: that eponymous duo of Roman Polanski’s brilliant early short, Two

Men and a Wardrobe (1958); undoubtedly influenced by Chaplin’s

slapstick antics. In this melancholic

comedy, our pair of pariah’s, always lugging a beloved wardrobe, just can’t

seem to find their niche in the modern city.

The Balloonatic (1923) is classic Buster Keaton. With gags galore, this film finds Buster bumbling

through each frame, finally whisked away by a rogue hot air balloon and dropped

into the woods to fend for himself. And,

finally, Buster’s balloon gives way to another: The Red Balloon (1956),

wherein a young Parisian boy’s best friend is his big red balloon. Theirs is a tender friendship only a special

sort of child could have, and one that ends up drawing the hostile attention of

humorless adults and envious peers. Before

the actual screening begins, we’ll be running Shy Guy (1947), an

educational film starring Dick York (of TV’s “Bewitched”), designed to bring

the antisocial adolescent out of his basement.

We similarly encourage you to emerge from yours, and enjoy—with us,

together--this evening of longing and laughter, melancholy and mirth.

Date: Friday, May 3rd, 2013 at 8:00pm

Venue: Oddball Films, 275

Capp Street San Francisco

Admission: $10.00 Limited

Seating RSVP to programming@oddballfilm.com or (415)

558-8117

Chaplin & Keaton

The films of Charles Chaplin and

Buster Keaton are black and white, and yet are remarkable for their many

figurative colors. The very phrase

“black and white” (as in “the issue is not so black in white”) is a perfect

emblem for the films of Chaplin and Keaton, as they are beguiling in their

seeming simplicity. Scenes that

foreground exaggerated physical comedy (i.e. “slapstick”) manage to resonate

with thematic meaning (whether political, social, or philosophical). Pictures whose dominant tones are joyful and

light are underscored with longing and melancholy, somehow all the more aching

for their subtlety. Chaplin and Keaton

are the cinema’s original on-screen loners—their films are both for and about

the isolated and alienated.

The

most celebrated of the Essanay Comedies, The

Tramp is regarded as the first classic Chaplin film. In his sixth film for Essanay in 1915,

Charlie saves a farmer’s daughter (Edna Purviance) and falls in love with her, but

upon the eventual appearance of her fiance, The Tramp takes off for the open road,

leaving only a note behind. The film’s

sad ending was new to comedy and incorporated Chaplin’s first use of the

classic fade-out, in which the Tramp shuffles away alone into the distance,

with his back to the camera.

Roman Polanski’s darkly

comic early film has many of the director’s thematic preoccupations already

present: alienation, crisis of identity, and a bizarre view of humanity that

sees us as some very strange animals. In

this quasi-surrealistic jaunt, two otherwise normal looking men emerge from the

sea carrying an enormous wardrobe, which they proceed to carry around a nearby

town. Seeking the right place to settle

and plant their furniture piece, all the two find is rejection at every

turn. Though they are two, they comprise

a sort of loner unit, shunned by everyone they encounter. Watch Polanski in a bit part he later

reprises in Chinatown). Two Men and a Wardrobe initiated Polanski’s collaboration with Krzysztof

Komeda (who would go on to score such Polanski films as Cul

de Sac and Rosemary’s

Baby), Poland’s great jazz

composer.

The

Balloonatic (B+W, 1923)

In The

Balloonatic, Keaton tests out hot air

balloons and wilderness survival. Keaton

is accidentally whisked away on a hot air balloon and stranded in the untamed

wild, rife with bears and white water rapids.

Fortunately he encounters a woman (Phyllis Haver) who is more adept in the

outdoors than he. The

Balloonatic was one of the last short

films Keaton made before moving on to features.

Despite its happy ending, a low-level sadness pervades this comedy, likely

due to Keaton’s eyes.

The

fairytale-esque story of an imaginative Parisian boy who develops a magical

friendship with a bright red balloon (the magical element is suggested by music

reminiscent of the score of The Red Shoes;

the color of the balloon likewise suggests this reference). He totes the balloon around the city, and

when in restrictive places (like his Dickensian school) where balloons aren’t

allowed, the balloon loyally follows the boy.

As the protagonists in Two Men and

a Wardrobe are met by ignorant onlookers with blind hostility, so too, the

boy and his balloon are targeted by mean spirited peers. This film won the Golden Palm at Cannes in

1956, and features breathtaking photography of Paris.

For the Early Birds:

Poor

Phil (Dick York of “Bewitched”) can’t seem to fit in at school. So he haunts his basement tinkering with

electronics like some ancestor of Crispin Glover. His overdressed dad comes to his rescue and

Dick learns a valuable lesson in social conformity.

Curator’s Biography:

Landon Bates is a UC Berkeley graduate of English literature and is the drummer for the two-piece band Disappearing People.